The £2.1bn Church of England Pensions Board is making great strides in adding illiquid assets to its portfolio. Chief investment officer Pierre Jameson tells Sebastian Cheek about a particular penchant for corporate loans, infrastructure and emerging market debt.

“[Triennial valuations] are very restrictive and I think there’s always conflict: if you’re a responsible investor, a long-term pension fund investor, you shouldn’t be taking a short-term view of performance.”

Pierre Jameson, Church Pensions Board

Why has the fund reduced its equity allocation over the past year and where has the money been reallocated?

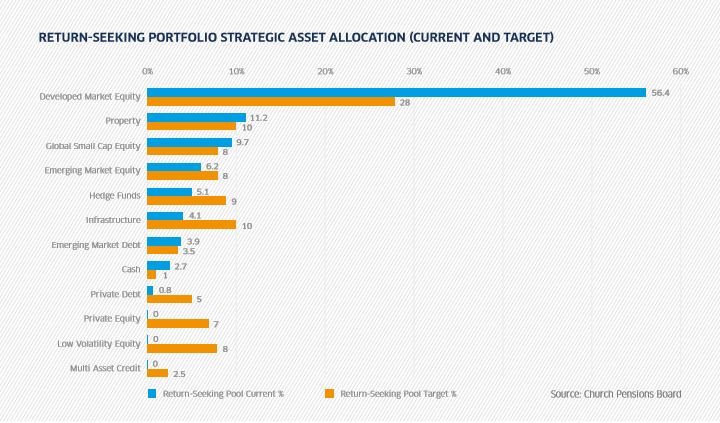

This is mostly still to happen, but in broad terms we are looking at private markets. So essentially non-equity investments, whether that’s infrastructure or private debt, which we have done some of and may do more in future. It also includes different forms of debt and possibly private equity. One of the reasons is to try to play the illiquidity premium more because our main scheme (for the clergy) is relatively immature, it’s still open and still enjoying new money and it has fairly long-duration liabilities. We believe something like 15% of our investments are ‘illiquid’ and a lot of the things we’re looking to do will take us more towards 30-35%.

Is there a point by which you would like to have that 30-35% in illiquid assets?

Two-to-three years, really, but we’re not tying ourselves down too much because sometimes it’s about taking market opportunities when they arise. So, it’s playing the illiquidity premium more and to play that best you need to be in private markets. And with private markets you’re not subject to mark-to-market rules to the same extent [as listed markets].

What is the benefit of not being subject to mark-to-market?

In many ways, marking to market is how risk manifests itself for a pension scheme. It’s not so much that the underlying assets themselves are risky, it’s the market’s view at any given time of them that’s the big variable. If you think about equity, the income return probably varies very little and the businesses of the underlying companies are actually fairly stable, so maybe there’s a 1% variance in those. Yet equity market pricing is probably around 20% per annum, so it’s to try to get to the true underlying return without that difficult public market wrapper.

How exactly are you accessing private debt and why?

We’ve committed £80m to Audax Senior Loans (ASL). I think the attributes of this US private debt investment are: it’s private markets, it’s illiquid and there’s no direct mark-to-market as such, because there’s no market for these loans. So there’s a sensible assessment of the ability of the borrower to repay, and that affects the valuation of the loan. As it happens, ASL’s record of managing defaults is highly impressive: it has seen just 0.04% per annum total loss across all portfolios since 2007. So, I think it’s one of these asset classes where credit risk has been rather overpriced, and I guess that’s the opportunity for funds like ours.

What are the risks of investing in US corporate loans?

These loans have a duration of anything between four and seven years, and obviously carry re-investment risk. That is because conditions will likely be quite different in seven years’ time from how they are at the moment and chances are you won’t be able to get Libor plus 6.5%. That re-investment risk is very pertinent if we were to start using the return on the portfolio as the discount rate for the liabilities and in a sense, you don’t get that sort of re-investment risk with equities because it’s more of a continuous market.